PART I: The Invited

AT 2.30 pm, we approach the blue door, on time yet aware we cannot enter unless invited in. These are the rules, they have always been the rules, and for as long as they remain the rules this blue door represents the barrier between us; the barrier between the house’s occupants and external harm. Behind it they wait, expecting us. There are two of them: mother and son. By now one, or maybe both, will have heard a car, a blue BMW, and will know therefore that we are here, waiting to be invited in.

Before a doorbell is touched, we see a figure at the window, confirmation that, yes, we have been seen. I imagine next, as this figure disappears, that they are considering how to repel the imminent threat, reaching, that is, for either garlic, a crucifix, or ash wood. Instead, a hand reaches for the door and it opens. We are then invited in, two vampires.

Inside the house, I watch Khalid look around, nervously rather than with menace. He is less a vampire in this moment than a man set to enter the sea with only his modesty protected. He follows one tentative step with another, yet fears that to continue will leave him shocked by the cold, hurt by the edge of a rock, or stung by a jellyfish unimpressed by the ease with which he has trespassed. He is not only undressed and exposed at this point, but he is also eager for any excuse to turn around and head back to shore, where it is dry, safe.

Our host, Denise, senses this and tries to now settle him with a smile. Smaller than him, but only in size, she permits him to hug her and from this hug, meaning from her, he draws all the strength he otherwise lacks. Grateful, Khalid spares her neck, convinced she is an angel. He tells her instead every detail about our four-hour drive from New Jersey to Maryland and Denise just listens. She accepts this is his way of coping, so resists the temptation to either interrupt or talk away her own anxiety, of which there is plenty.

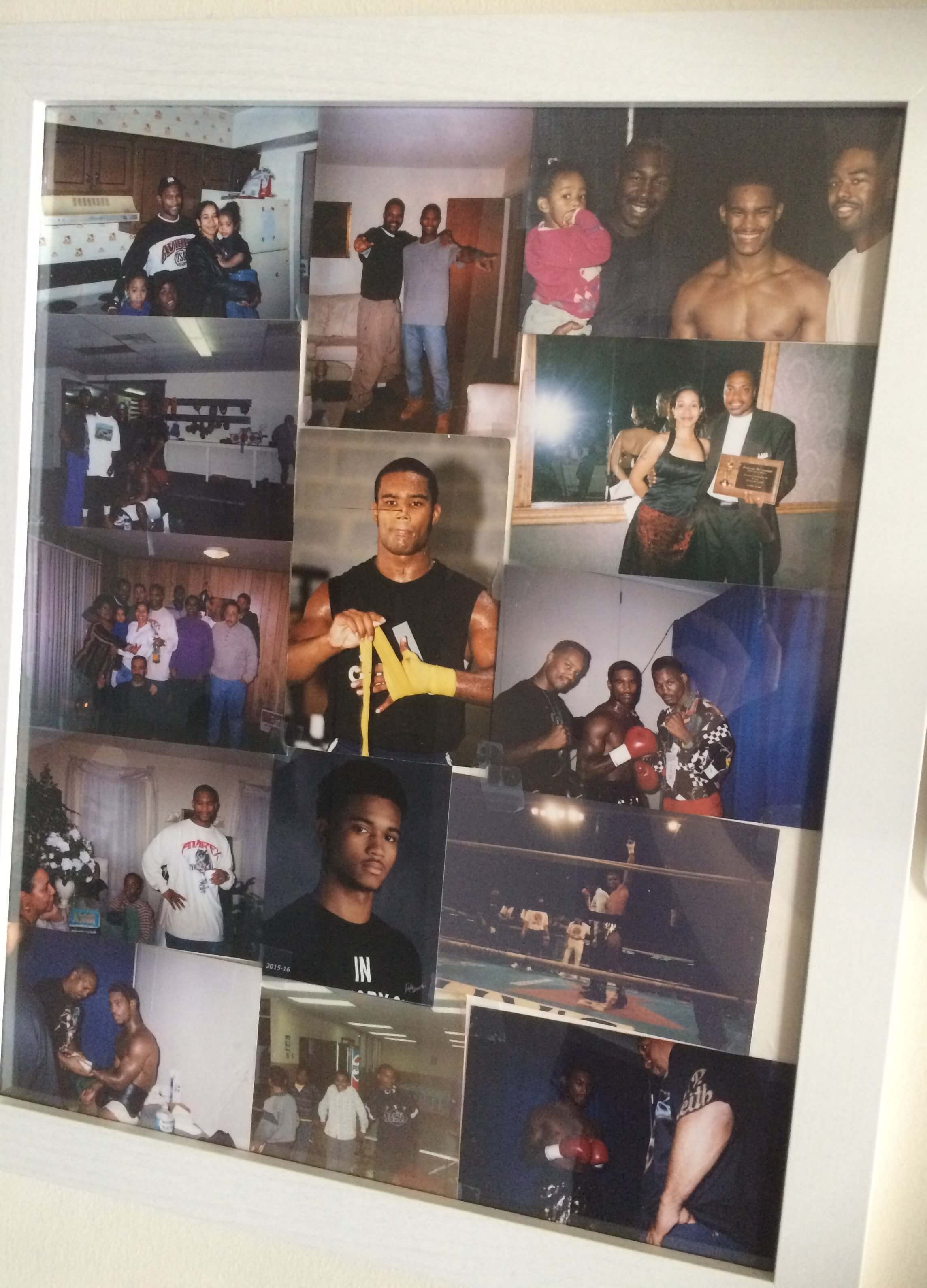

I watch her watch him as she watches him look everywhere but at her. I suspect, too, that as he looks everywhere but at Denise he is seeing her husband wherever he looks, including on the wall. That is where for almost two decades he has lived and where you can today find framed photographs of him: montages of him training and on fight night. (In gloves, he looks mean, ready. He looks exactly as he did back then: young, carefree, full of life.) There on the wall he never ages, forever twenty-six.

He also lives in Denise Scottland’s heart and in the features of her son, Bee, who is eighteen years old and presently at the dining table eating the fried chicken his mother cooked before we arrived. It is a meal he intends to finish before going to work, we learn, and between the finishing of this meal and the starting of his shift he greets us with handshakes. “Who does he look like?” Khalid says as they step back from each other. “You look so much like your dad.”

This Bee already knows, of course, so need not be told. Like the man who tells him, Bee sees the same pictures on the wall and, although he never got to know the man in these pictures, he sees them every day and sees himself staring back every time. “I know I do,” he says. “I know I do.”

Denise smiles, certain Khalid means no harm. “Come through,” she says, inviting us into the living room. We follow, two vampires.

II: A Good Game

In order to discuss death, we enter a living room. It is a room made in its owner’s image: clean, calm, everything in its right place. Yet today it has guests, one of whom feels out of place. Already, in fact, there is a sense he has gone too far, overstepped the mark. He feels eyes on the wall following him, narrowing. He suspects they want to know what he is doing here. Moreover, when he will leave. He is then told to sit down and only because it is Denise who has told him, and only because her voice lifts in adjuration, does Khalid sit down.

In the chair he now leans forward, as if primed to run when hearing a gun. It could be a starting gun or one aimed at him. His reaction would be the same. On edge, he tries to forget his own unease and make the others feel comfortable. He tells Bee, the son, that he likes to know about people’s history and says, “I want you to know I care about you.” He just as soon shrugs, worried he has come on too strong. He adds, as a kind of retraction, “I ask questions of all my customers. I don’t like big crowds. I can sit in a one-on-one thing but if you get me with fifty people I freeze up.”

“I’m the same,” says Bee, a relief to Khalid. “The crowds don’t bother me, though.”

The root of his fear is terrorism, Khalid explains. Every time he goes over the George Washington Bridge in one of his delivery trucks, or through the Lincoln Tunnel, he wonders if today will be the day someone “tries something”. He calls New York the biggest target but the safest place and Bee claims to understand what this means.

Bee, it turns out, is also in transport. “I’m working in NIH (National Institutes of Health); patient transport,” he says. “I transport patients throughout the hospital from unit to unit. I enjoy it. I didn’t even know anything about the hospital when I joined but I heard they had Ebola patients there. That turned out to be a myth.” He shrugs. “They’re really big on doing research for HIV, AIDS and sickle cell. I also transport blood and urine throughout the hospital. It’s a pretty interesting job. I’ve only been there a month, but I heard NIH is really big around this area, so I think I’ll stick down this path. If it’s God’s calling, I’ll end up being a GM or something.”

Khalid smiles. It is a doting smile. A proud smile. It is also a smile he fails to supplement with words, therefore what follows is the thing he wanted to avoid: silence. “I know you like Kevin Durant,” he now says, apropos of nothing.

“I love Kevin Durant,” says Bee.

“I thought about you when he went down. I thought, Oh boy. I didn’t want to see him go down like that. When he went down, I thought about you. I think he came back too soon.”

“Yeah, he came back too soon. That messed him up. I wasn’t really upset Toronto won, though. I wanted them to.”

“I’m sorry your boy went down. I know you like Kevin Durant.”

“Oh, he does,” says Denise, her input welcome. If nothing else, it shows Khalid’s conversation with her son is one of which she approves, with the topic of sports – sports other than the one that has both broken the three of them apart and brought them together – considered safe terrain.

“I love football,” says Khalid, staying safe. “I don’t have no team, though. I just jump from bandwagon to bandwagon. If they’re winning, I’m winning with them. I used to be a fan of teams but I ended up losing so much money from gambling that I ended up hating all of them. I hated teams. I hated players. I used to hope their plane would come down if they lost me money on games. I was losing my family because of those guys. That’s why I don’t pick a team anymore. I just like to see a good game.”

“I used to play basketball,” says Bee, “and I was a diehard football fan. But it just wasn’t for me. I guess God was like, ‘Nah, this isn’t for you.’ I was having too many ankle and knee problems. I still play the sport for fun but that’s about it. It went out the window after that.”

Khalid, nodding his head, can relate. “One time,” he says, “I was playing and had this big guy right in front of me. I closed my eyes and he ran over me and got the quarterback. The coach said, ‘Go home, son, this ain’t for you.’ Those are some big guys. Six-seven. They don’t care. They smash you and break you. Ain’t no big thing. My son got hurt really bad playing football. He got a laceration right by his kidney.”

As the conversation continues in this vein mother and son, both silent, remain enchanted by its triviality. They let Khalid talk and wonder how long he will keep talking until he runs out of stuff he feels obliged to say and focuses instead on what he wants to say.

“I’m gonna go take a nap,” Khalid says next. “I’m working all the time. I can’t sleep past five or six in the morning. I don’t get much sleep. I’m going to let you guys talk.”

“Do you want to lie down in one of the rooms?” asks Denise.

“No, it’s okay,” says Khalid. “I’ll go out to the car.”

“Okay.”

“I’m going to call my son. He’s going through this phase where he gets mad at me for any little thing. I could buy him a shirt and he’ll get mad at me. He’ll say, ‘Dad, don’t buy me nothing!’” He now stops, remembers, realises. He reminds himself that father-son talk is not welcome here. Not at a time like this, in a house like this, and in present company. “Denise, I love your house,” he says by way of a handbrake turn. “I really do.”

“Thank you,” she says, aching to tell him it is okay.

III: It’s Just a Sport

In the silence left by his departure I am told something Khalid himself could have done with hearing before he escaped. “We love boxing,” says Bee. “We watch it all the time.”

To then prove it, the teenager goes on to name Maryland’s Gervonta Davis as his favourite fighter, and also expresses admiration for the likes of Manny Pacquiao, Keith Thurman and Errol Spence. His mother, meanwhile, admits, “At first, initially, it was a little hard for me. But as time goes on, no, it’s fine. It’s just a sport.”

In their situation perhaps it can be nothing else. It has to be a sport just to allow them to move on, rationalise it, and accept its history, its future, and its ubiquity. It is, whether they like it or not, a fixture of American life, something they would likely stumble upon when switching channels on their television even if doing all they could to avoid it. Besides, to hate it is to change nothing.

“I’m actually doing it now,” says Bee, meaning boxing. “There’s a lot of mixed emotions about that. Some say do it, some say don’t do it. But it’s really my choice. I get where they’re coming from, but I still want to do it. People always want to tell me it’s a dangerous sport.” He rolls his eyes. “I already know it is. I know that more than anyone. But because of that I train hard and I’m focused. I train hard every day. I think the parents know how dangerous boxing is but the kids who participate in it to get in shape or compete don’t witness the tragedies that my family did. That’s the last thing they think about. Normally the goals are just about being world champion and winning fights. That’s it. They don’t think about what could go wrong.”

He trains at a gym called Champion Boxing and, at the time of this conversation, has been going for only three or four months. He is enjoying it, he says, and has already done plenty of sparring, yet his mother knows more than anyone that he still has a long way to go. It is in this awareness she finds comfort, hope.

“I enjoy it, getting knocked upside the head,” Bee says, a glint in his eye. “I’m a southpaw, just like my dad. I’m actually right-handed. I try to be an all-rounder. I hope I’ll be able to fight, I really do.”

Finally provoked, Denise shifts forward in her chair and clears her throat. “I’ve got mixed emotions,” she says. “He’s got to take his own path at the end of the day. At one time it came and I expected it. Then it went away. But I knew it would resurface. We’ll see.”

Truth is, Bee was so young at the time of the incident he never had the questionable privilege of being cajoled into it, or pushed that way by the man he now attempts to emulate. Instead, his interest in boxing is an effort to fill in gaps, or locate pages torn from a book Bee, its reader, has every intention of finishing. He is encouraged not by a presence but rather an absence; the advice he hears are words only he can hear. “Yeah, he’s the inspiration,” he says of his dad. “We’ve got collages of him in here. We’ve got his trunks framed. Every day I look at that and it’s a reminder.

“If he hadn’t been a boxer, would I want to box now? I have no idea. But he’s definitely the inspiration. He always has been. Everybody says ignore the noise. If you want to do it, do it.”

His mother side-eyes him. He can feel it just as I can. “I watch his fights all the time,” he says, undeterred. “I watched his fight with Bernice Barber (a draw in 1996). There’s like two of his fights on YouTube and I watch them sometimes. He was a great fighter. I hear a lot of stories from coaches and stuff. They come up to me and tell me about the kind of person he was.

“It’s just hard because every time you look up Beethaeven Scottland on the Internet it always says this is the boxer who died in the ring. I don’t like the fact he is remembered just for that. He should be remembered for so much more. In this area he is remembered for more than that. We actually went to an event that honoured him about five years ago. That was nice. It’s really good his legacy still lives on in the boxing world.”

Just as Bee opens up, I am a vampire again. I am a reminder of what he wanted to forget; a reminder that his father was indeed that boxer who died in the ring that time. It is a fact hard to ignore, in truth, particularly on account of the company I keep and the man I brought to their door, but steering the conversation towards boxing feels suddenly insensitive. Better to focus on mothers and sons, I think, the only kind of parental relationship this boy has ever known.

“She’s the best mum in the world,” he says, causing Denise to blush. “I couldn’t ask for a better mum. It’s definitely been hard growing up as a young man without a father, but my mum has done a wonderful job of raising me. I have no criminal record. I graduated on time. She was on me.” He thanks her with his eyes. “I think all kids have it hard growing up and going through changes in life but doing that without a father is very difficult. I used to have a very aggressive attitude towards everyone. I was mad at the world for what happened. But as you get older you start to mature and see things differently. It just takes time, especially in today’s world. Dads are just not in the picture at all today. You kind of feel like a statistic… but my situation is a lot different.” He then pauses before adding: “Sometimes, whenever I’m going through something, I think about what my dad would tell me. That’s always there. I always want to make him proud. Everything I do is dedicated to him. I’m carrying on his legacy. That’s what I wanted to do with boxing.”

“I don’t think you need to follow in someone’s footsteps to continue their legacy,” says Denise. “He (the father) already has his legacy and he (the son) has to create his. It has to be a heartfelt passion, just like his dad’s legacy. If he doesn’t have that, and he wants to do it for the benefit of someone, that’s going to show. It’s going to show that it’s not wholehearted and that you’re doing it for someone else, even though you love that person and want to make that person proud.

“But your dad will love you and be proud of you regardless of what you do. That’s what I try to instil in him. Don’t think you have to walk in his footsteps because, honestly, I really don’t think his dad would have wanted him to walk in his footsteps. I think his dad would have wanted him to grow and go further and be so much more than what he was. His dad had a really hard life. He’s going to be proud of him regardless.”

On that note Bee gets up from the chair and gives his mother a hug. It is a hug not of acceptance or acquiescence but rather one of farewell, love. It is something they do every time he goes to work, fuelled no doubt by an appreciation that nobody knows when a hug between two people will be their last.

“When I was younger, I actually hated the sport of boxing,” Bee admits before leaving. “I actually didn’t like him, either,” he says of Khalid, the man outside. “It’s just the principle of it. I looked at it like this: he killed my father.

“But my mum always told me that boxing is a business and to not take it personally. They all have a dream and stuff like that.

“As I got older, I actually gave him a call. I told him there were no hard feelings and I could sense he was happy I made that call. You can just tell when someone’s happy on the phone and I knew it. You can tell someone’s smiling on the other end and he was, I’m sure of it.

“He always said the call from my mum was very sincere, but I think he was more surprised by my call. I’m Bee’s son. It was a very heartfelt moment of forgiveness. Forgiveness is very widespread, especially in this household. He sends me stuff and I talk to him now and again when I’m not busy. It’s like the situation never happened.”

“I believe it,” says Denise, her eyes closed. “I believe it.”

IV: The Will and the Way

Before Little Bee, there were two Bees: the one Denise knew, and the one he told her about. The one she knew she knew inside out and better than anyone, whereas the one he told her about – the vulnerable child – always broke her heart in a way Bee, the husband, never could.

Raised not by parents but his boxing coach, Dereck Matthews, the Bee Denise would never know had neither clothes nor shoes before meeting Matthews and often fetched dinner from trash cans. He was so desperate in those days, in fact, that hunger inevitably led to stealing and stealing to a short period in jail. Denise, smiling, explains: “He told me he was in the jail cell and said to God: ‘Father, if you make a way for me to get out of this, I promise you I will never steal again.’ I don’t think it was nothing big” – she pauses to now laugh – “but he got out and he never stole anything ever again. He didn’t want to go down that path and have a record. He used to always tell me that boxing was his discipline.”

To an extent Denise gave Bee something similar. Not discipline, perhaps, but certainly direction, structure, a purpose, all things boxing claims to provide in return for your soul. They got together, she says, when Denise was twenty-six and living in DC. That is where Bee was born, his neighbourhood North Brentwood, yet by the time they were dating he resided in Riverdale.

“Our family grew up with his family,” Denise says. “I used to live in the same building as his aunt. I was always close to his cousins.

“Bee would come around sometimes, but he was younger, more like a baby. Time goes on, you grow up, you go your separate ways, but you still stay in contact with some family members. His cousins would come over to our house all the time and we would always hang out together. His brother and my sister started talking and next thing you know they got engaged and were planning their wedding.

“One day Bee called the house because he wanted to talk to his mum who was at our house that day. I think his cousin answered the phone and he asked about me. He said, ‘Oh, she’s here.’

“Ever since then we just talked. He was like, ‘You want to go out sometime?’ I said, ‘Yeah, okay.’ But it was no big thing because I already knew his family. Even though he didn’t come around often as a child, I still knew him.

“Of course, now I know why he didn’t. He wasn’t there with the other kids. He was with Dereck. It makes sense now.’

Boxing, his other love, was no secret. Denise knew about it, she respected it, and she could see the positive impact it had on Bee’s life. “You’ve just got to support them and allow them to be who they want to be,” she says. “When you meet someone, if you want to be with them, you have to allow them to be who they are. You’ve got to support the dream and the goal.”

A reluctance to give up on his boxing dream led to Beethaeven Scottland both winning fights and losing fights. It led to him taking opportunities others would have passed up, then fighting beyond the call of duty. This invariably put him at risk, never more so than when agreeing to fight George Khalid Jones on June 26, 2001, on board the U.S.S. Intrepid in New York. Scottland was, at the time, a super-middleweight, whereas Jones was a light-heavyweight. He also took the fight on just four days’ notice after David Telesco, Khalid’s original opponent, broke his nose.

“I think back to that night a lot, to be honest with you,” Denise says. “I think it has shaped and moulded me. To experience something like that has to change you. You never get over the hurt; it’s always there, the pain. You just adjust, accept, and live with it. But I do think it moulds you and shapes you into a different being. You become so much stronger. That’s not to say I wanted to become a stronger person, or wanted to become the person you see today, but I had no choice in the end. I had to get strong. I had to become the person you see today. I had to adjust immediately.

“That was my mindset at the funeral. When that day was over and it was time to walk back to the car, I was like” – she claps her hands – “let’s get on with this. Of course you are going to grieve, and you’ll have to go through that process, but I had these little children. You have to do what you have to do. That’s how I’ve lived my life, even with my sons. I understand this, I understand that, but let’s keep it moving.

“I was never scared. I just always had the mindset that I had to do what I had to do. Bee always used to have this saying and I think about it all the time. He used to say, ‘Where there’s a will, there’s a way.’ He would say, ‘You’re the will but I’m the way.’ I always think about that.

“I wouldn’t wish it on no one. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy and I don’t have enemies – at least not ones I’m aware of. But if I did, I wouldn’t wish grief like that on them. It was an indescribable feeling. You know how when you’re in a relationship and then break up and you actually feel pain and feel like you’re going through something? No. You’re not. Nothing compares. I mean, when something like this happens to you, you actually feel it. It actually feels like your heart is broken. It’s broken inside of you. You try to do everything you can just to ease that pain. All you want is to get some normalcy going again.

“In time, you start living every day normal but inside of you is complete turbulence. You can’t sleep. You’re tossing and turning all the time. You say, ‘Okay, let me put the TV on. Let me breathe a little bit.’ It just doesn’t go away from the time you get up to the time you lay down. You watch the TV but you’re not really watching it. You can’t stop thinking about it.

“It took years, but I got to a point where I accepted it. You never get over it, but you no longer feel that pain. I do think it’s still with me, though. I don’t feel the pain now, but the hurt is still there. It always feels like something is missing.

“The worst questions are the what ifs? What if this happened? What if he was still here? They never leave you. But I didn’t ever think, Why me? It just felt like an out-of-body experience and I don’t even know what one of those feels like. I guess you’re somewhere watching you. It’s like, is this really happening? No, it can’t be. It wasn’t like I was in a fog. I really wasn’t. I remember talking to God one day and I said, ‘Okay, Father, I’m ready to wake up because there is no way this has really happened.’ That’s how it was for me. It was a permanent state of shock at first.”

Maybe the quickest way to come to terms with the reality of the situation was to make contact with the one person who had been as affected by what had happened as Denise. They were, after all, now bonded, inextricably linked by virtue of a tragedy.

“Oh, he definitely became part of our life,” she says of Khalid, still outside in the car; out of sight but never out of mind. “I don’t know, one day I was on my way to the store – this is the true story, exactly how it happened – and I was getting ready to go when I heard the Holy Spirit say: ‘Call Khalid.’ I thought, okay, I’ll call him when I get back. Then I heard it again and this time it was more like: ‘Call Khalid now.’

“So I thought okay, let me call. I called and I believe his wife, Naomi, answered the phone. I asked to speak to him but of course me and her talked first. I just wanted to let him know that everything was fine and that I didn’t hold any grudges. At the end of the day, he was there to do a job, just as my husband was there to do a job. I don’t think that it was anything personal.

“I could just sense that he was going through something. I hadn’t heard anything. I hadn’t talked to anybody. Nobody said he’s going through this, he’s feeling this way, he’s this or he’s that. I guess all of that would be quite normal, so it was probably easy to assume that was the case, but I knew nothing about him or his situation at that time. For me, that wasn’t the reason to pick up the phone.

“I don’t think forgiveness was hard for me. It was only a month or two after the fight when I called Khalid. But what I never did was walk around angry at him. I never went through that. I was just numb, that’s all. I was just trying to deal with my own hurt. I never felt anything like that towards him. I was never saying, ‘Oh this man did this or did that…’ I never experienced it.

“He tells me that call changed his life. But I just told him everything was okay and to not give up on his dream. I told him to keep going. I said, ‘Bee is in heaven right now. He is not holding any grudges. I’m pretty sure that if that’s your dream (to continue fighting) and that’s what you want to do, Bee would want you to do it.’”

With Denise’s say-so, Khalid did indeed continue with his career, though was, in truth, never the same. He won fights, but never as convincingly as before, and the ones he lost were often the result of him either refusing to throw enough punches or struggling to find the right ones, the really hurtful ones, when confronted with a wounded opponent.

“I became a fan of his,” says Denise, who was ringside when Khalid fought Darnell Wilson to a draw in Glen Burnie in 2004 “I was happy to see him fight. I was in good spirits. It’s so funny, people were coming up to me and saying, ‘You know, I really have got to take my hat off to you. I couldn’t do it.’ These were men. I said: ‘Really, you couldn’t?’ They said: ‘No, I couldn’t do it. I understand about forgiveness and all that but I couldn’t do it.’

“It’s easy and natural for us to stay in touch. As I always say, ‘He’s just little old him and I’m just little old me.’ When we get on the phone together, we just chit-chat and have our little talks and it’s like nothing ever happened. It’s as if we’ve been talking all the time. We talk about his past. He tells me about it, and who he was, and I still can’t see it. I can’t see how the person who is in my house today is the person who did all those things back then. They are two different people.”

V: Mummy’s Boy

As much a test as a gift, Denise sees in Bee, her son, the man she loved and the man who lives now only in the faces of other people and in the pictures on the wall. The more time that passes, the more alike her son and husband seem to get, and the more she is then reminded of both what she has lost and what together they once managed to create.

“He’s been easy-going,” she says. “He had his spurts growing up and at middle school he was often either angry or upset; the littlest thing would get him upset. But he just didn’t know how to deal with certain situations. Some children had fathers and obviously he didn’t have one. I remember he always used to say to me that sometimes he would be around his friends and they would say, ‘My father and my mum are getting on my nerves,’ and he would always say to them back, ‘You’re lucky you have both your parents. You should look at it that way. Both of your parents are living.’ I know that bothered him for a while.

“I also feel like he’s missed out on quite a lot. He always says his mother did a good job, but I don’t think I could ever instil in him what his father could have instilled in him. There are just some things mothers can’t do. We can’t connect in that same way. I wonder sometimes, in fact I know, that if his father was here, he would be a totally different person. I know that for a fact. I think he would probably be edgier and a little more rough. He’s a mummy’s boy, definitely. If his dad was living, he wouldn’t have been a mummy’s boy. He would have been a daddy’s boy. He would have been siding with him on everything.”

Her other son, Delgado, is six years older than Bee and currently at work. He was six at the time of his father’s death, therefore aware of it, yet Denise says he coped “okay”. Bee, too, coped okay, she says, although she struggles to shake the comment he made just before he left for work.

“That was sad to hear that,” she admits. “He never at the time, when he felt like that, would talk about it. When me and Khalid were on the phone and he knew, he would never be like, ‘Oh Mum, I don’t know why you’re talking to that man when he did what he did to my father. I don’t like him.’ No, he never showed that.

“I was shocked one day when he just came out and started talking about his feelings. I talked to him about forgiveness, but I’ve always talked to him about forgiveness. We went away, didn’t talk about it anymore, and then one day out of the blue, when he was maybe fifteen or sixteen, he just said, ‘You know what, Mum, I’m going to call Khalid.’ I said, ‘Oh, yeah?’ He said, ‘Yeah. I think it’s time.’ I said, ‘Okay, that’s fine.’ But I never pushed him into calling him. I never said he should think this way or that way. You have to give a person their time to go through what it is they need to go through.”

She attributes her own ability to go through what she needed to go through to two things: one, her “normal childhood” and stable upbringing, which, if compared to Bee’s, somehow makes his demise all the more tragic; and two, her faith, one of many things the Scottlands shared.

“The only person who could tell me it was going to get better was God,” she says. “In my prayers I thank Him for helping me make a way for me and my children but most importantly keeping me in my right frame of mind throughout all of it. I know often when people go through tragedies and trauma they do self-destruct. They turn to drugs, alcohol. They get into bad patterns of behaviour. It happens all over. But I just thank God that never happened to me.”

In terms of the day to day, and a more tangible presence, Denise credits her parents for helping her get through that testing time in her life. She calls them her “rocks” and in so doing remembers that her husband was for much of his childhood without rocks of his own. It is then the doorbell rings and she smiles. She knows who is at her door. “I better go let him back in,” she says.

VI: Cleanliness

While waiting for them to return, I wonder if Khalid, as planned, managed to sleep in the car. “I don’t like nobody to know my birthday,” I hear him then say, carrying into the living room a conversation started at the front door. “My wife threw me a surprise birthday party once and I didn’t like that. I’d rather be the one giving a gift than receiving one.”

“It’s funny you say that,” says Denise, as though gossiping with one of her girlfriends, “because I don’t think I know how to receive. It’s like I’m so used to giving that I don’t know how to react when I receive something. I feel so awkward when somebody says, ‘Ok, here you go.’ I almost want to apologise.”

“Now you feel like they’re one up on you.”

“Yeah.”

I smile as they sit down; Khalid in one armchair, Denise in another. “They give you a cup of soda and now you’ve got to give them two cups of soda,” says Khalid.

‘Exactly.’

“It bothers me too. I’m like that too.”

“I’m so used to being the giver and doing what I have to do.”

“On my birthday I used to give my mother a gift. That was my way of saying thank you to her. When she died, I smiled. I thank God for her.”

“Amen.”

For the next hour Khalid and Denise speak comfortably and without interruption. Denise, who earlier claimed her true calling in life was to be a counsellor, mostly listens, while Khalid, one of twenty-six children born to a man named Eddie Bolden, begins by telling Denise that growing up he saw his father just twice a year: once in the summer, when he would give Khalid a ride on his motorcycle, and once before Christmas, when Khalid and his siblings would receive twenty-five dollars apiece. Otherwise without one, Khalid was robbing at seven, on probation at nine, ferrying drugs to New York at thirteen, had a shotgun forced down his throat at fourteen and, by fifteen, was routinely smoking crack cocaine. He did so on the couch with his father, the one who had him selling it on the streets.

“My mother,” he says, “would clean nice homes. She’d go there for three or four hours and the lady who owned one of the homes would teach me how to read. I was twelve. I admired her for that. She cleaned out the toilet and the bathroom and that would be her pay: a lady teaching her son to read. She did maid’s work.”

“Yeah, my mum did that too,” says Denise.

“Your mum’s from the south?”

“Uh-huh.”

“That’s a common job there.”

“Growing up she was over in Virginia cleaning for people. As she got a little older, she started working in a government building.”

“My mum was very happy when she was cleaning in the hospital and got away from the south,” says Khalid. “I was just happy because she made the sacrifice for us as kids to go and clean homes every day. I have a lot of respect for her for that. She made thirty dollars a day.”

“I think my mum did too.”

“Your mother still alive?”

“My mother is still alive, but she has dementia now.”

“God bless.”

“She has dementia and Parkinsons.”

“Okay.”

“And my dad just passed away in July of last year.”

“I’m sorry. My mother passed two years ago. It was the happiest moment of my life. I was back and forth to jail and I was so happy she got to see me as a very responsible person. Every time she called me for something I would run there. In my mind every time you help your mother it’s a blessing from God.”

Denise can’t help but laugh. She explains: “When I was growing up and dating, I would always think, What is it with these mothers and sons? I used to always think that. But then lo and behold God gave me two sons. It’s like they just had a connection, a bond. You can’t break that bond.”

“As a kid,” says Khalid, “my mother used to cry to me: ‘Please don’t get in trouble this week.’ She used to beg me. Why should your mother have to beg you to stay out of trouble?” He now stares at the floor, pain etched on his face. “On a Sunday, she would say, ‘Please go through this week without getting suspended or getting in trouble with the police.’ But there wasn’t a week that went by where I didn’t give her a hard time.”

“Wow,” says Denise.

“That’s why when she died, I said, ‘Thank God I was there with her and they weren’t bringing me from prison in handcuffs to see her.’ That was always my nightmare. For seventeen years of her life, she got to see me calm and responsible, always with my kids. I always visited her at her house to sit and talk with her. She always laughed.

“Now I’m just happy seeing my mother die and her seeing me do great things. That was the best gift God could have given me. I’d rather pray for you to get some of yours.”

“You’re at peace,” says Denise. “That’s it.”

“I am, Denise. I couldn’t sleep before. I’d wake up at three or four in the morning and could never get back to sleep. Now I go to bed at eleven and by eleven-o-one I’m out cold. I’m at peace.

“It took a lot of years to get there, though. I was ignorant. I was envious. If I saw someone with something I wanted, or they were doing better than me, I’d be like, ‘How can I get that?’ I used to also wish I was white and was embarrassed to say that. White people are more privileged. I would say, ‘Why couldn’t God make me white?’ I thought all the cards were against us. I hated God every day because of how He made me.

“Now I thank God for who I am and for allowing me to become a better person. I dealt with the causes and made my bed with Him and lay in it. I got better once I was able to talk about my envy and jealousy. Only when I talked about it did the healing process start.”

Because Denise continues to just stare and smile, Khalid, still fearful of silence, adds: “Yeah, I wanted to feel how I feel today. You know how you feel when you’re reborn? I go to sleep in thirty seconds. Naomi (his wife) will be like, ‘How do you do that?’ I really don’t know. I don’t even have to think about it. I could take a nap anywhere. My mind is clear now. I do appreciate you, Denise. I want you to know that.”

“I appreciate you, too,” says Denise as Khalid again looks around the room. “I’m just so happy,” he says. “That’s why I talk so much. When I was depressed, I didn’t talk at all. And when I talked a lot in the old days, it would always be about who we were going to rob, how we were going to rob, selling drugs, or the next scam. It was always something negative.” He shakes his head as sadness sneaks up on him. “I swear to you, Denise, me making this trip, you’ll never know what it means to me. Thank you. Where I am spiritually, coming down here, when I go to sleep tonight, I’m going to be on cloud nine. Naomi says I smile in my sleep and that’s because I’m with the angels. The angels must be saying, ‘Yeah, you had a good day today.’ I used to see my son smile in his sleep and I’d say, ‘There must be an angel with him.’

“When my mother died, I smiled for days. I was so happy she got to see me like this. I miss her so much but I’m on a natural high. I know you don’t need drugs now to make you feel like this.” Once more he acknowledges the tribute to Beethaeven Scottland, his former opponent, on the wall. This time, too, he is less afraid, even pointing in its direction. “I like this wall,” he says. “Denise, I appreciate you.”

“I appreciate you, too,” says Denise, the closest thing either of us have known to an angel.

“I’ll pay for him to do a realty course if that’s what he wants to do,” Khalid says, speaking now of Bee, her son.

“Okay,” she says, “if that’s something he wants to do.”

“If that’s something he wants to do, let me know right away. It’s easy to pass the test. I passed the test but I couldn’t get my licence because of my record. But I still got the experience to go on and do things with it. I went in 2003, I think, and years later I finally got to use the knowledge. I didn’t get the licence but they couldn’t stop me using the knowledge to secure commercial real estate. I think it would be a good idea for him, trust me.”

“Okay,” Denise says, laughing. “I thank you.” She follows this with a shrug as they both get to their feet. “At least it’s not boxing.”

On that matter Khalid speaks only once we have left the house at 5.30 pm and returned to the car. It is out of respect, I think, that he chooses to refrain from sharing his opinion with Denise. Either that or fear. “I can understand why his mother finds it hard to let him box,” he says. “I wish he was living my way; I would love to train him. But I wouldn’t want him to box neither if I was her. You find yourself in a bad round and get hurt – then what? But those are her feelings. Every little boy wants to know what it was their father did for a living. Some want to follow them and carry on that legacy. You have to also understand her point of view, though. She went through something bad once and I’m sure it would kill her to have to bury her son. I don’t think she would be the same.”

We soon hit traffic and I watch as Khalid takes a green tube of Pringles and tips the contents of the tube down his throat. In the process he holds the tube high, via its base, and with his hands touches neither the crisps inside nor the tube’s rim. He calls himself a “clean freak” and says certain habits were passed down from his mother. He has today never felt cleaner.

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (8)