“The greatest line of boxing commentary I ever heard was not from a professional boxing commentary.”

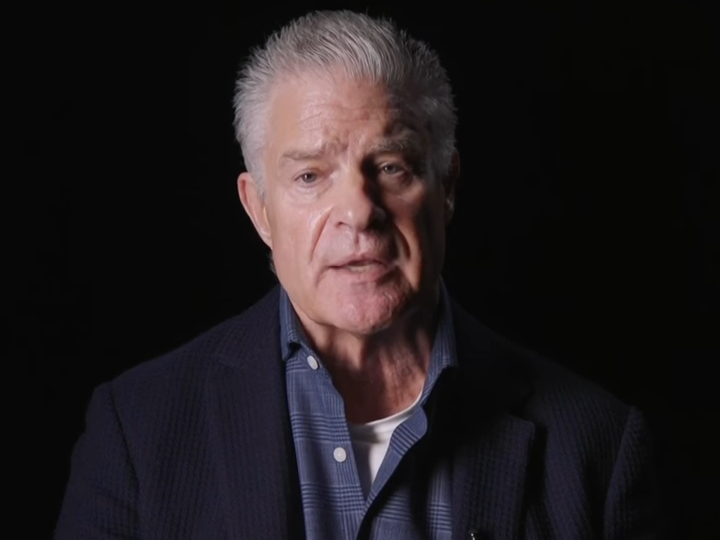

Jim Lampley, for so long the voice of HBO Boxing and now the purveyor with BoxingScene’s Lance Pugmire of live text commentary for PPV.com, is sitting in the media center at the MGM Grand contemplating this Saturday’s super middleweight meeting between Canelo Alvarez and Edgar Berlanga when he begins a reminiscence that will allow him to illustrate the point he is about to make.

“Have I told you this story before? It’s in the book.” Now 75 years old, and after a little more than five decades on ring aprons and sidelines, Lampley has written a book – titled, after perhaps his most famous line of commentary, It Happened! (and subtitled “A Uniquely Lucky Life in Sports Television”) – that is scheduled for release in April; and, perhaps as a result of reliving his life in his head for publication purposes, he finds multiple reminiscences within easy reach.

Even so, this particular recollection rapidly takes an unexpected turn. The aforementioned greatest line of boxing commentary he ever heard was, he says, “from Mick Jagger.”

OK, didn’t see that one coming. Please continue.

“I was in a conference room in the ABC building in New York in 1980 as part of a crowd that Roone Arledge had assembled to watch the closed-circuit feed of Muhammad Ali versus Larry Holmes,” he explains. “And if you are a smart critic of the sport, you know that this is going to be a gradual and eventually gut-wrenching beatdown. So, in about round eight or nine of the gradual and gut-wrenching beatdown, I'm standing watching the screen when I feel a little poke in my rib cage. I look to my right, and it's Mick. I had met him at the Montreal Olympics in 1976, so he knew me. And he looked at me and said, ‘Lamps, do you know what we're watching here?’ And said, ‘No, Mick, what are we watching?’ He said, ‘It's the end of our youth.’ Nothing Larry Merchant ever said was more profound than that. And I'm pretty sure I'll go to my grave saying the greatest line of boxing commentary ever, right, came from Mick Jagger.”

The point of the story, he continues, is that, all too often, our favorite fighters – the ones we have maybe grown up watching and idolizing, or whose careers we have followed from the very beginning – stay on too long, and our once-great rivals end up being humbled and hurt by opponents who once upon a time might not have caused them even the slightest of inconveniences. And one day, he notes – maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but conceivably soon – that may well happen to Canelo Alvarez. Indeed, with 65 pro fights under his belt and with no stoppage wins in almost three years, it seems clear that Alvarez is, depending on the analogy you want to use, on the home stretch, on the back nine, or entering the final rounds of his long and storied career.

“Someday it may happen, and Mexican fans will have to accept that it happened,” he says. “Like Oscar De la Hoya getting taken apart against Manny Pacquiao on a night when a lot of ringsiders really believed that Oscar was too big, Oscar was too strong, Oscar could withstand Manny's dynamism and speed, etc, etc. At the end of the day, he got into the ring, and he had nothing.”

Should that day come, if it does, there will be plenty of critics carping from the sidelines that Alvarez was never really that good anyway, that he cherry-picked opponents or waited for them to get old. As Canelo edges toward the finish line of his career, where might heultimately rank when he hangs up the gloves for good?

By way of answer, Lampley offers another story.

“It's very interesting to me that recently, I was at the International Boxing Hall of Fame induction ceremony. And I spent the whole weekend hanging out with Marco Antonio Barrera and Eric Morales,” he begins. “Back in the day, you would never hear somebody say, ‘I spent the whole weekend hanging out with Marco Antonio Barrera and Eric Morales,’ but that was the fact of the matter. They were more or less arm in arm all weekend, just verifying and underlying something I always say, which is this sport is ultimately about falling in love. It looks like brutality. It looks like life and death. It looks like two guys are trying to kill each other, but they're really falling in love. Classic case in point: Mickey Ward and Arturo Gatti. But anyway, I asked them about Canelo. And Erik said – and Marco agreed – that Canelo has a logical case to present as the greatest ever Mexican fighter. ‘Greater than Salvador Sanchez?’ They said Canelo has a longer resume and a more varied resume. ‘Greater than Ruben Olivares?’ More dimensions, more different things that he can do in the ring. You know, they had justification. And again, he has a case to present.”

But if the wheels do one day come off, when might that day be? Might it conceivably be on Saturday against Berlanga at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas?

“The only way, in my view, that Berlanga wins the fight is if Canelo gets old overnight, and we've seen it happen,” he says. “But I don't think it's gonna happen.” In fact, he offers, such is Canelo’s control of his own career and surroundings that he might in fact be one of the few, like Lampley’s former colleague Lennox Lewis, to buck the trend and to retire while he’s still on top.

The fact that Lampley – and he is hardly alone – is struggling to conceive of a path by which the undefeated Berlanga might overcome Canelo inevitably raises the issue with which the Mexican’s critics, and even some of his fans, have been raising with greater frequency and intensity: that Alvarez has apparently decided his legacy is secure and that he is perfectly content to run out the string against unthreatening opponents while the likes of David Benavidez are forced to turn elsewhere. That frustration only increases each time Alvarez simply shrugs off such critiques with the casual disdain with which one removes fluff from a sweater.

“I don't think he pays much attention to, or invests a great deal of emotion in, what I say about him, what you say about him, what people in boxing say about him,” Lampley offers. “When somebody stands up at that podium and criticizes him, and other fighters tear into why he's overrated and how they can beat him, etc, etc, then maybe he listens. Maybe he stores it away in some secure box inside himself. But you're never going to see an outward response that says, ‘You got to me.’ That's not him.”

As anyone who has dealt with Canelo in any kind of professional capacity can affirm, Alvarez is among the most self-possessed and self-aware of individuals, taking on life on his own terms and acutely aware of his own strengths and weaknesses. It is one reason why Lampley suspects that the Mexican may avoid the debilitating denouement to his career that has bedeviled so many – but also, he believes, why Alvarez will blame nobody but himself when and if that time does come.

“Somebody was smart enough, and I want to say, artistic enough to convince him as a young man that everything in life was going to be his responsibility, that he would rise and fall according to the judgments that he made and the decisions he made as to what he was going to do,” Lampley suggests. “And that was the only way that he could, particularly in a profession like this one, go to bed at night, secure in the understanding that, whether it was all the glorious wins or the two losses that are on the record, he was the one who decided to put himself in that ring. And he, more than virtually any fighter I know, has the right to that level of self-satisfaction. And it helps me to be secure that when he reaches someplace toward the end, and as is almost inevitable in this sport, the apple cart comes apart, the apples all roll out on the street, and people say the next day, ‘Oh yeah, he was terrible,’ when all that takes place, he will have no one else to blame but himself. And I think he likes it like that.”

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (3)