In 1998, a Japanese man, Tomoaki Hamatsu, or Nasubi (meaning “eggplant”), was locked in a tiny apartment, alone and naked, on the pretense that to escape all he had to do was enter a variety of mail-in sweepstakes in magazines until he won ¥1 million (or $8,000). Achieve this goal, he was told, and the people behind Susunu! Denpa Shonen, a reality-television show, would then release him, give him back his clothes, and allow him to return to the world from which he had been snatched.

Naturally, all the time he was “participating” Nasubi was cut off, oblivious to the machinations of producers. He had no communication with human beings, no way of protecting his modesty, no form of entertainment other than magazines, and nothing to eat save for crackers given to him to prevent him starving to death and whatever he managed to procure from the magazine competitions he entered. Oh, and he was also being filmed; his every move and breakdown shown by Nippon Television to 17 million viewers each Sunday night.

Of that small detail Nasubi was totally unaware – unaware, that is, until he was set free 15 months later and saw before him a studio audience. It was then that Nasubi, now famous, came to learn what everyone else had known for a while. He learned that the rules had changed during the show, hence the length of time he spent in two different apartments (one in Japan, another in South Korea). He learned that he had been set up, duped. He also learned that the only thing that had protected his modesty was an animated eggplant Nippon Television would stick on screen for each Sunday night broadcast.

At the time this was considered revolutionary television, further proof that the Japanese were at the cutting edge of entertainment. To sleep at night the show’s producers would simply tell themselves it was all a social experiment and that it was in the public’s interest to observe, in real time, the slow and painful unravelling of a man robbed of all human contact and everyday necessities. Better yet, any reservations they may have had were assuaged by the number of people watching, evidence that they were merely providing what those in Japan desired.

Now, of course, the show is viewed differently, through a wider lens. Now we have seen Big Brother and various other shows predicated on the notion that the fragility of a human being is something to poke, prod, and pillage. We have also seen shows in which contestants are tricked for an audience’s entertainment, including one show in which six British men attempted to woo a Mexican woman in Ibiza only to later discover “Miriam” in fact had a penis. Again, this was supposed to be funny at the time. A real gotcha moment. Great for TV.

In 2024, it is considerably tougher to trick contestants and audiences in the same way. This is because we now like to believe we are suddenly purveyors of good taste and that what once passed for entertainment in the nineties and noughties no longer has a place in civilized society. And yet, in conflict with this is the fact that we are these days desensitized and not as easily shocked, meaning the reality TV of today has to be politically correct but also inventive; inventive enough to at least grab our attention and stop us from scrolling.

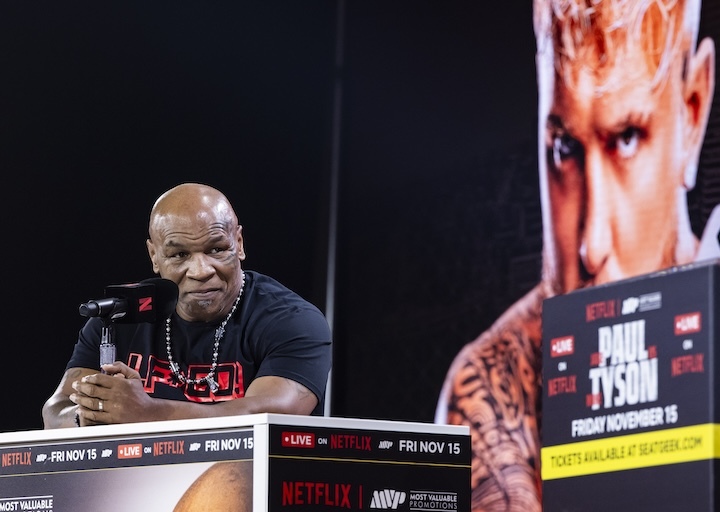

In boxing, that means Jake Paul, more reality show producer than boxer, exhuming a 58-year-old Mike Tyson to “box” him on Netflix. No better place for it, you might say, this spectacle does indeed contain all the key elements of a successful reality show. There are, for a start, celebrities involved, two of them. One is “old famous” and the other “new famous” and both bring large audiences with them. They need only tap something on their phone to guarantee the entire world pays attention and that, in this day and age, is all you really need to green light a project like this.

Better still, rather than damaging someone by having them partake, the damage here is already done. Here, in fact, the trick is not to revel in Mike Tyson’s damage but instead play down the extent of it so he makes the walk and receives more of it on fight night. In other words, just as in the past reality show contestants might have been duped by a show’s conceit to secure their participation, the same applies here. In this instance, Tyson, as if a patient in a care home whose fantasy life must be embellished by nurses, is reminded at every turn that he is a boxer. Not a retired boxer, but an active one. A frightening one. A dangerous one. A boxer who has every right to believe he belongs in a ring at the age of 58. “Yes, Mr. Tyson,” they say. “You are still The Baddest Man on the Planet.”

Similarly, Jake Paul, someone whose entire life is a reality show, will be seduced by the same conceit. He too will be led to believe that he is a boxer. A frightening one. A dangerous one. A boxer who has every right to believe he belongs in the ring despite never learning how to properly box and boxing mostly non-boxers. “Of course you can beat Canelo Alvarez,” he hears daily. “He is running scared.”

This, in truth, has been the story of Jake Paul’s pro boxing career to date; one of smoke and mirrors; one of sycophants telling him only what he wants to hear; one of coddling in the name of clout. He has been fed a lie just as Mike Tyson is now being fed a lie and on November 15 they will both play dress-up and be watched by millions, including those who claimed they would turn away. They will wear gloves like boxers and they will move like boxers – one hampered in this quest by old age and the other by sheer incompetence – and they will together make ungodly sums of money. Then, as the world watches it unfold, or implode, we will ask ourselves, “Who is fooling who here?” We will wonder whether Tyson and Paul are the fools for believing they belong together in a boxing ring, or whether in fact we are the fools for watching them pretend and rubbernecking simply because everyone else is doing the same; simply because covering it, or publicly expressing an opinion on it, “does numbers”.

Ideally, to save us from ourselves, what we could really do with on November 15 is an animated eggplant. We could do with one so big it not only protects the modesty of Mike Tyson but also conceals the face of the reality show producer plotting to further damage him in order to enhance his own fame.

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (16)